Jose Antonio Vargas (Activist, Writer, Producer) | Renegades

Redefining the American Dream, on the page to the stage

Welcome to Renegades, a series spotlighting Asian Pacific leaders and creatives who are carving their own paths and defying stereotypes along the way.

This week, we sit down with Jose Antonio Vargas, activist, producer, author, and founder of Define American. Jose discusses his thoughts on the American Dream, storytelling for immigrant artists, and his latest book White Is Not a Country.

What did you want to be when you were growing up, and how does that compare to what you do today?

I emigrated to the U.S. when I was 12. When I got here from the Philippines, I was immediately fascinated and confused and energized. Where am I? Who am I here? Who are these people around me? I lost myself in stories, reading them in newspapers, magazines, books, plays; consuming them on TV and in film; listening to CDs and cassette tapes of Broadway musicals. Public libraries were my Google. I practically lived at the Mountain View and Los Altos public libraries. I studied how Mike Nichols, Billy Wilder, Sidney Lumet, Stephen Sondheim, August Wilson, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, et al, told stories––the what-how-why of the stories they were telling.

Incredibly, now my work is all about storytelling: telling them myself, either through writing, producing, or directing (books, theater, film), and trying to understand how stories can inform, liberate, and connect. When it comes to stories, my goals are education, freedom, and connection.

As a co-founder of Define American, a narrative change organization utilizing the power of storytelling to humanize immigrant stories, how did your personal narrative and challenges of concealing your immigrant status catalyze this initiative?

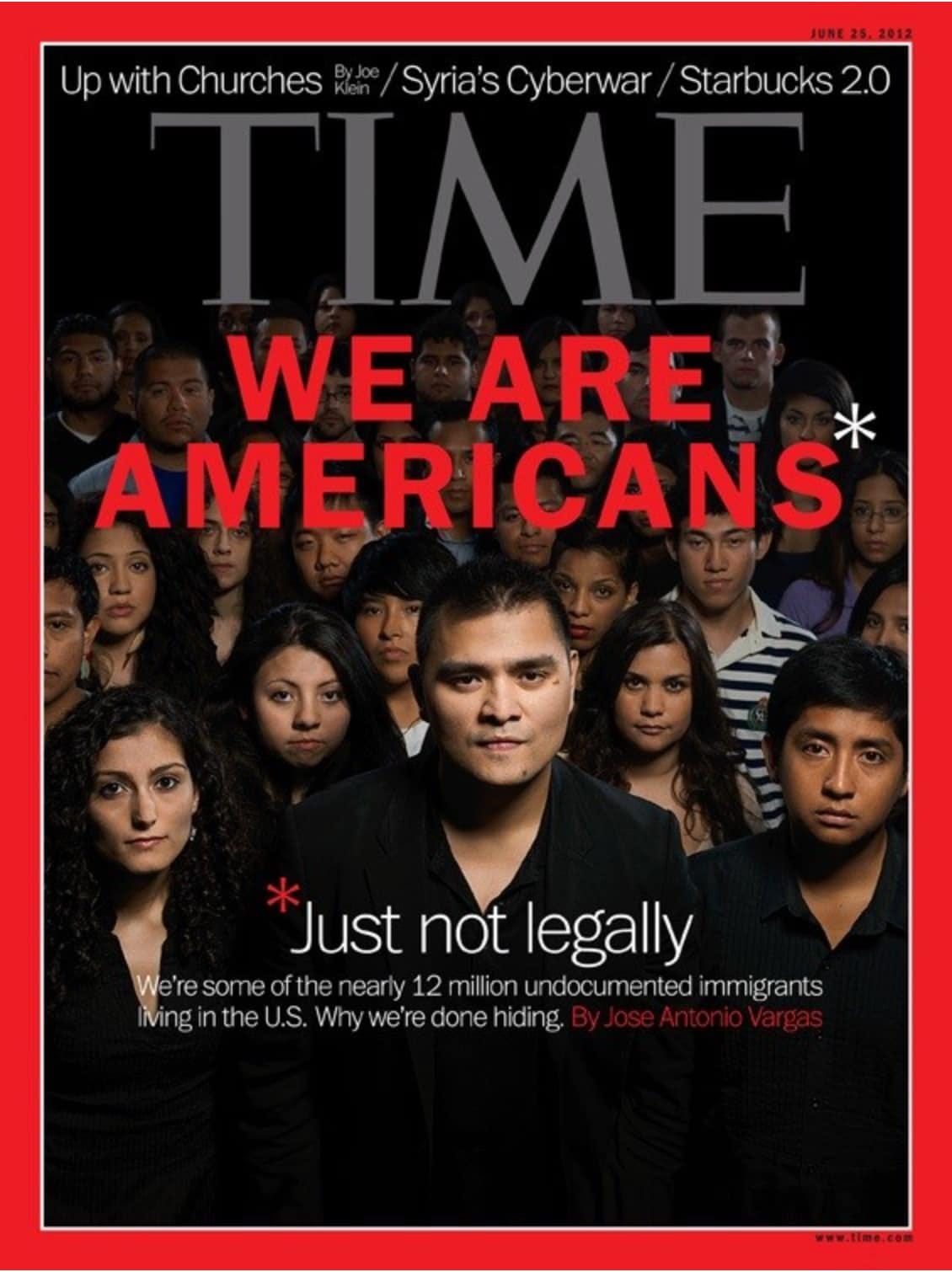

“Coming out” and telling my story as an undocumented, gay Filipino American gave birth to Define American. But mine is just one story––a very complex and specific one. We need more complex and specific stories to humanize the immigrant narrative that, on the whole, is flooded in misinformation and disinformation, and lacks humanity.

Immigrants are more than workers, more than labor. Immigrants are remaking and replenishing what has historically been a White country that has marginalized, systematically and structurally, Black people, Native Americans, and other people of color, who are now mostly immigrants from Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Many embark on the journey to America with hopes and dreams. Reflecting on your journey and the countless stories you’ve heard, how do you perceive the evolution of the “American Dream” for immigrants over the years?

The “American Dream” has gotten more complex as the country has become home to millions of immigrants and our families since the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. And it should be more complex. Where do immigrants fit in the racial, economic, and cultural mosaic of the country? Are we melting into some melting pot? Or are we just creating our own salads?

Your memoir, Dear America, provided a candid look into the life of an undocumented immigrant. As you approach the release of White Is Not a Country, how does this book build on or diverge from your previous writing?

They are definitely building off each other. White Is Not a Country is much more reportage and research-driven than Dear America. I started writing my memoir as the Trump presidency began, and I wrote it with the intention of self-deporting from the U.S. (The first line was: “I do not know where I will be when you read this book.”) When I finished the manuscript, I found out that the school district I attended as a child was renaming one of its elementary schools, and that my name was being considered. To my surprise, my name was selected. So, what do I say to the students there? That I was leaving the country I call my home because it got too hard? That was one of the chief reasons why I decided to stay. White Is Not a Country is an extension of my asking the questions of: Where do immigrants––documented and undocumented, of all racial backgrounds, but particularly Asian, Latino, and Black immigrants, and mixed race peoples––fit in our country’s foundational Black and White racial binary?

Journalism is my religion. I ask questions. I love research. I seek to connect dots and people. In some ways, White Is Not a Country is a culmination of my journalistic work. I’m struggling to finish it!

Your accolades extend beyond journalism to championing equity in education, especially for the undocumented. Given your association with the California State University Board of Trustees, what are some of the pioneering initiatives or changes you’re looking to champion to promote inclusivity and equity?

The CSU is the world’s largest public university system: 23 campuses (including Cal State Los Angeles, Cal Poly, SF State, where I am a proud alumnus), almost half a million students, many of whom are from working class immigrant families. 1 in every 20 Americans holding a college degree is a CSU graduate. And because of its size, CSU is home to the most diverse immigrant student population in the country, documented and undocumented.

I was not surprised that I was first regularly appointed undocumented Trustee. (Undocumented students have served as Student Trustees.) But after Governor Newsom appointed me, I was really shocked and a little embarrassed to know that I was the first Filipino who’d been regularly appointed, given how many Filipinos have graduated and currently attend the CSU. Filipinos are the largest AAPI immigrant group in California, and we’re among the largest ethnic groups in the country. It made me think how important it is to create a pipeline for Filipino leaders to serve on Boards, both public and private.

As for my role as a CSU Trustee, it’s an eight-year term, and I intend to be as strategic and impactful as I can be. I was really fortunate to have been appointed at a time when Wenda Fong, a pioneer in the AAPI community––she’s a badass, in the very best sense of the word––is serving as Chair of the Board. In fact, Wenda is the first Asian American woman to serve in that position. I’m learning a whole lot from Wenda, just witnessing how she leads. I have some ideas on how to promote equity and inclusivity within the CSU, and it’s too early in my term to discuss them in detail.

From earning a Pulitzer Prize for journalism to receiving Emmy and Tony nominations, your journey across multiple platforms is remarkable. How do you navigate and choose the most fitting medium for each story or message?

I aim to be creatively borderless. I may not be able to physically travel outside the United States. (I haven’t left the U.S. since arriving here in 1993; if I leave, there’s no guarantee I’ll be allowed back.) So when I decided that I would stay, that the U.S. will continue to be my physical homebase, I challenged myself in making sure my storytelling work was limitless and borderless. It’s books. It’s theater. It’s film and TV. It’s helping lead Define American and ensuring that we can support immigrant storytellers and storytellers who want to tell immigrant stories.

One of my favorite artists, the film and theater director George C. Wolfe, once said: “Movies are for stories. Television is for characters. Theater is for ideas.” That was really insightful. And what about books? And podcasts? And YouTube videos? Marshall McLuhan was correct: The medium is the message. And I intend to keep investigating which medium is most effective in telling specific and complex stories that humanize people.

How do you envision storytelling as a tool to foster empathy and reduce polarizations in the current societal climate, and what doors will it open for immigrant artists in the future?

Storytelling may be the only tool to promote empathy and break down walls and barriers. That’s why it’s important that we support storytellers––all storytellers. Last month, the Board of the Pulitzer Prize expanded its eligibility criteria for music, drama, and book awards to include everyone, regardless of immigration status. This is huge for a couple of reasons. The first is that, too often, we are defined by who we exclude––and why. At Define American, we believe that a human being’s immigration status does not define one’s humanity, nor limit an artist’s creativity. And who we honor is a measure of what we value. The secondary reason is that the Pulitzer’s decision will have repercussions for all sorts of prizes, scholarships, and fellowships that artists depend on. Define American worked with prize-winning writers Javier Zamora and Ingrid Rojas Contreras and the amazing organization Undocupoets to make it possible.

Also, earlier this year, Define American published “Creativity is Boundless: An Inclusive Guide” to help arts organizations make funding opportunities more accessible to immigrant storytellers.

The Broadway musical, Here Lies Love, is a historic moment celebrating the Filipino community. What significance does this musical hold for you, and how has collaborating with such a vast number of Filipino producers influenced the production?

You gotta love America: still no immigration reform, still no legalization for millions of undocumented immigrants like me, but, hey, I can be a Broadway producer! Being one of the lead producers of this groundbreaking Broadway musical––groundbreaking because of the concept and design itself––we took out all the orchestra seats and created a nightclub inside a theatre––and groundbreaking because of the story it’s telling––disco meets despotism, unpacking how people can be seduced by leaders, and showing how everyday people can stand up and fight for democracy––has been one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences for me. Life-changing, truly. I feel like I’m getting an MBA and a MFA at once. It’s helped me think about how to better navigate being both an artist and an entrepreneur.

And to do this work alongside the first-all Filipino cast on Broadway, and to be amongst the largest collection of Filipino producers ever assembled for a Broadway show! My producing partner Clint Ramos likes to say that not a single decision, macro or micro, about the show has been done without someone Filipino. That’s crucial, given how culturally specific the show is. We’ve just told Broadway, which is foundational for the entertainment industry (many playwrights are TV writers, casting directors go to Broadway shows to cast TV and film roles): Asian people––the world’s majority population––are not interchangeable. This show is about Filipinos, and it stars Filipinos, and it’s produced by Filipinos. That’s historic and revolutionary.

What are you currently working on that’s exciting you the most?

Finishing White Is Not a Country!!

Lightning Round

Daily habit: Watching a Michelle Kwan skating video on YouTube

Most used emoji: raised eyebrow emoji 🤨

Most productive time of the day: I write best in the early morning

Fun fact: I’ve visited 49 of the 50 states: I can’t wait to visit Alaska!

Favorite Broadway show: if not Here Lies Love, it’s Sunday in the Park with George